|

|

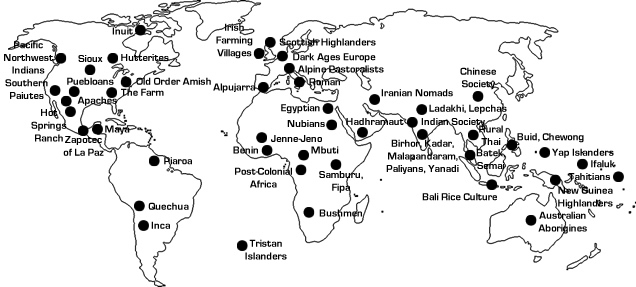

Alternative Lifeways Across Space & Time

North America

Inuit

Pacific Northwest Indians

Hutterites

Sioux

Old Order Amish

Southern Paiutes

Puebloans

The Farm

Hot Springs Ranch

Apaches

Maya

Zapotec of La Paz

South America

Piaroa

Quechoa

Inca

Europe & Atlantic

Scottish Highlanders

Irish Farming Villages

Dark Ages Europe

Alpine Pastoralists

Alpujarra

Roman Empire

Tristan Islanders

Africa

Ancient Egypt

Nubians

Jenne-Jeno

Post-Colonial Africa

Samburu

Fipa

Bushmen

Asia & Pacific

Iranian Nomads

Ladakhi

Lepchas

Chinese Society

Hadhramaut

Indian Society

Birhor

Kadar

Malapandaram

Paliyans

Yanadi

Rural Thai

Batek

Semai

Buid

Chewong

Yap Islanders

Ifaluk

Bali Rice Culture

New Guinea Highlanders

Tahitians

Australian Aborigines

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We members of dominant societies provide aid to less fortunate people around the world, and our affluence, our science and advanced technology, seem to prove our superiority. But as noted above, we have our problems, too – many of them serious. Is there anything important and useful that we can learn from other societies of the present, or even of the past?

|

|

|

|

Examples

These examples of human societies and their alternative behavior patterns are a work in progress and are by no means complete, but they are more than adequate to demonstrate universal patterns and reveal universal insights about our species, while suggesting an endless variety of successful approaches to life on earth.

The dominant Anglo-European society is a special case. Due to the legacy of colonialism and the power of their technology, Anglo-European society is global. It completely dominates Europe, North and South America, Australia, and much of Asia. Even in areas where Anglo-Europeans remain a minority, such as the Middle East, East Asia, South Asia and the Pacific Islands, and Africa, the Anglo-European economy and technology are dominant.

But despite the global political, economic, and technological dominance of Anglo-European society, alternative societies remain and often thrive as social and ecological "islands" in the midst of the dominant culture, often achieving surprising autonomy and independence.

Whereas at first glance these examples may seem to include incomparable "apples and oranges", we all participate in both the macro and micro levels of society, and it's vitally important to understand the relative effectiveness of local vs. global institutions. And, when we learn what works, we may wish to reform our society or even to design our own society, so it's important to look at intentional communities both historic (Amish) and modern (The Farm) as well as those which have evolved chaotically over millenia (Anglo-European and Southern Paiute).

Full disclosure: Max has direct personal experience with the following societies: Anglo-European, Pacific Northwest Indians, Southern Paiutes, Hot Springs Ranch, Maya, Amish, Yoruba, Scottish Highlanders, and Berber. For knowledge of the rest, he is indebted to anthropologist John Reader, the Peaceful Societies project of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and individual anthropologists including Conrad Arensberg, John Hostetler, Carobeth Laird, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, and many others.

|

|

|

|

Top

|

|

|

|

Model Sociologists and anthropologists haven't been able to agree on a model for comparative study of human societies, so I've developed my own generalized model based on Pictures of Knowledge, referencing various scholarly studies for completeness, but introducing some unconventional twists in hope of teasing out some new insights.

For example, my model of human societies is inspired more by human ecology than by sociology or anthropology. Until recently, ecologists focused primarily on natural habitats, omitting humans from the ecosystem, and anthropologists traditionally distinguish human societies from their natural environments, treating their technologies as a form of "material culture" rather than as ecosystem interactions.

Also, anthropologists focus on race, language and kinship structure, which I've found to be mostly irrelevant when studying social and ecological success. And they tend to treat religion and myth as distinct from social control, whereas both religion and origin stories are directly implicated in social control for most societies. Finally, although communication and transportation technology are central in modern societies, anthropological studies often overlook or under-represent distance interactions – communications, travel, trade – between groups or settlements in traditional societies.

| Topic |

|

Subtopic |

|

Details |

| |

|

|

|

|

| History |

|

World |

|

Their mythology or creation story |

| |

|

Society |

|

Evolution of the society |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat & Ecosystem |

|

Habitat & Ecosystems |

|

Surrounding Landscape, Occupied Landscape, Climate, Ecosystems & Natural Resources |

| |

|

Neighbors |

|

Adjacent Societies |

| |

|

Land Use |

|

Settlement Patterns & Technology, Mobility |

| |

|

Ecological Interactions |

|

Subsistence & Other Technologies |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Society |

|

Overall Structure & Institutions |

|

Overall structure of the entire society, overall management, institutions, population control |

| |

|

Internal Connectivity |

|

Internal Communication, Travel, Trade |

| |

|

Life Cycle |

|

Birth, Parenting & Childhood, Adult Providers, Mating, Elders, Death |

| |

|

Behavior Management |

|

Social Codes, Religion, Knowledge & Wisdom, Leadership & Decisionmaking, Conflict Prevention & Resolution |

| |

|

Resource Distribution |

|

Economy & Sharing |

| |

|

Healthcare |

|

How they care for each other's mental, emotional & physical health |

| |

|

Neighbor Relationships |

|

External Travel, Trade, Intermarriage, Conflict, etc. |

| |

|

Crisis Management |

|

How they respond to & resolve crises that affect the entire community |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Summary Observations |

|

Strengths |

|

Values, Behaviors & Institutions that contribute to their social & ecological health |

| |

|

Weaknesses |

|

Values, Behaviors & Institutions that undermine their social & ecological health |

|

|

|

|

Top

|

|

|

|

Previous | Next |

|

|