Friday, May 27th, 2016

Monday, November 7th, 2016: 2016 Trips, Great Basin, Regions, Road Trips.

The Mystery Begins

Many years ago, while idly researching the mountains of Nevada online, I stumbled upon someone’s article about an alpine plateau featuring unusual lakes. The lakes had been given a pretty name, and the plateau was described as an idyllic and seldom visited place, a little-known jewel of Nevada wilderness.

I mentally filed this away, but somehow instead of fading from my memory, it became a mystery that beckoned to me over the years. I’d had a terrible summer this year, unable to hike and enduring a lot of pain due to complications from hip surgery, and while spending hours each day working hard on therapy to recover, I dreamed of a camping trip in the fall which would be my reward for all the hard work.

But when I searched online for information about the plateau and the lakes, I could find hardly anything. The original article had apparently been taken down. Google Maps confirmed the existence of the plateau and one of the lakes, but satellite imagery didn’t actually show anything up there. The most I could find was that these mountains were supposed to be covered with nearly impenetrable thickets; there were no informative photos available.

People interested in ghost towns and old mines claimed to have visited the foothills below the plateau; their photos just showed a few shacks and shafts situated in low, barren, scrub-covered hills that could have been anywhere in the desert.

Going through my ethnographic library on the Nuwuvi – the tribe I’ve become most familiar with – I found that these mountains seemed to be on the northwestern border of their territory, where they mixed with the Western Shoshone. This made me even more curious to find out what kind of place it was, what kind of a home it would have been, and whether there remained any sign of their presence. Did they use the plateau and the lakes, or even camp up there?

Nuwuvi Country

Just getting to the mountains themselves – let alone to the plateau – turned out to be a challenge in itself. The first day was a long drive, ending dramatically in sunset thunderstorms over the Colorado River Valley. Along the way, I picked up a GPS message device that had been recommended by one of my wildlife biologist friends. Both friends and family had worried for years about my solo trips into remote areas, and as much as I resent satellite technology, with my mother’s birthday coming up, I thought she might appreciate the gift of knowing where I was, and that I was okay.

The second day began in the rain-soaked Mojave Desert basins along the Colorado River, through fresh air saturated with the wonderful tang of creosote bush, under a blue sky with unusual pillows of cloud floating only a few hundred feet above the ground, followed by a reluctant plunge into urban sprawl to grab lunch and shop for provisions. Finally, in early afternoon I found myself heading up the storied Pahranagat Valley, a lush oasis where the Nuwuvi had farmed, hunted mountain sheep, and preyed on the thousands of migratory waterfowl that use the beautiful Pahranagat Lakes. Now, the lakes are part of a federal game preserve managed in cooperation with the tribe. I had passed them 25 years ago but had never stopped, so I pulled over to watch the birds, and took a short detour to check out the visitor center.

There, the first thing I discovered is that the local Paiutes claim that the abstract style of petroglyphs common across the Mojave was created by their ancestors. This contradicted what my friend, a desert archaeologist, had told me earlier this year. He maintained unequivocally that the nomadic Nuwuvi were only capable of faint, chaotic scratches here and there, and that the more iconic, patterned rock art had been made by the more “advanced” Patayan, ancestors of the settled Yuman Indians of the lower Colorado River Valley, a radically different culture. Who do you believe? I respect my archaeologist friends, but I’ve always thought it preposterous that we white people should be the ones to write everyone else’s history.

By the time I’d driven the length of the valley, the sun was setting behind the mountains to the west. I clearly wasn’t going to reach my destination today. After a night in an over-priced motel, I was looking forward to camping, and I knew that mountain passes in the BLM-managed desert often have side roads where you can find a secluded, informal campsite. That’s the attraction of BLM country – you can camp anywhere, unlike in Forest Service jurisdiction where you’re likely to end up in a campground crowded with RVs and growling with the noise of generators.

Sure enough, after a half hour of scouting, I located a dirt road that meandered back through the slopes, and ended up two miles away from the highway, in a gully with a couple of small junipers for a windbreak and a small level patch for my sleeping bag. It also had a nice view of wild, open country and distant mountains to the northeast.

I started a cooking fire with twigs that would make just enough coals to grill the lamb sausages I’d picked up along the way, and watched the stars come out. With nothing to do after dinner, I went to bed early and slept like a log.

In the morning the entire landscape, including my truck and my gear, was covered with one of the heaviest dews I’d ever seen. The temperature was just above freezing as I made breakfast, rubbing my hands together to warm them up. When the sun rose above the hills and its light reached my campsite, I spread my sleeping bag and tarp over the nearby sagebrush to dry, but I had to wait another hour for everything to dry out enough to pack away for the drive to the mountains.

Lost Canyon

It was all beautiful country, with its endless flat basins, dazzling dry lakes, and rugged mountain ranges, each dramatically different, but my destination turned out to be even more remote than I’d expected. It was noon by the time I turned off the highway and headed back toward the mountains on a dirt ranch road. I could see that the ghost town people had been totally off – nothing in this landscape looked anything like their photos, so who knows where they really went. I was heading into a beautiful, intimate basin of multi-colored, semi-forested small peaks, with the pinnacles and rimrock of the heavily-forested main range rising steep and dark behind. There was no sign of a ghost town, or for that matter any human structure at all, not even a fence or corral. And farther back, I could just barely glimpse some higher, barer slopes, apparently above treeline – the lost plateau?

My only map that showed this region in detail was a 40-year-old USGS map which showed a maze of old mine roads crisscrossing this basin. The map turned out to be mostly incorrect, but after trying some abandoned side roads that quickly became impassable, I finally connected with a freshly-graded gravel road that climbed and twisted back toward the massif. Suddenly, cresting a rise, I saw light dazzling off the windows and metal roof of some kind of fancy chalet, perched on a peak at the entrance of the easternmost canyon, to my left. The canyon I hoped to follow to the plateau was to my right, and the road trended between them.

After another mile I ended up faced with a locked gate, behind which I glimpsed a cleared pasture and a big lodge-style ranchhouse only partly visible through the trees. So someone had their own private Shangri-La all the way back here, at the mouth of a spectacular canyon! I turned around and found an ungraded side track that seemed to head toward the canyon I was more interested in, and sure enough, within a half mile I came to another locked gate, beyond which the road seemed to lead into my canyon. There was no “No Trespassing” sign here, and when I got out for a closer look, I could see that no one had driven through this gate for many years, and the fence to either side of it was untended and decrepit.

I backed my truck into the trees beside the road, made myself a quick lunch, and packed my rucksack for one or two nights of trekking. On the map, it looked like an easy hike: about four miles to the plateau, with about 2,000′ of elevation gain. It was 2 pm, and I expected to easily reach the plateau and set up camp well before sunset.

The first mile or so did turn out to be easy – just following the abandoned dirt road as it meandered into the canyon, back and forth across the dry creekbed, and up through the low forest, to where the floodplain narrowed and vanished. Tall thickets of coyote willow glittered golden in their fall foliage, surrounded by stands of rabbitbrush, some still blooming yellow. There were no structures, no trash, so sign of humans at all except for the eroded dirt road, and the remains of an ancient wooden water pipe coming down from some source up canyon. And there was no sign that cattle had ever been back here; the fence had probably been built to keep them out, not to keep them in. But beginning at the mouth of the canyon, the ground was covered with signs of wildlife: abundant tracks of deer or bighorn sheep and small mammals, and scatterings of their scat everywhere.

Thickets and Mazes

The challenge began when the road ended and the canyon proper began. By choice, I do my wilderness explorations in areas with no man-made trails, areas where I have to scout and choose my own path, and I never carry a compass, since I normally hike in open desert and navigate by sun and topographical landmarks. But the old USGS map wasn’t detailed enough to show the landmarks in this completely unfamiliar place, and contrary to the few photos I’d seen online, this range turned out to be heavily forested. I’d just have to stick to the main canyon and pay close attention, reading and memorizing the landscape along the way.

Only a few yards beyond the end of the road, I hit my first impasse. The canyon bottom was only a few yards wide, and choked with solid thickets of tall, golden-leaved coyote willow. And the steep slopes of the canyon sides were forested all the way down to the bottom with pinyon and juniper trees whose low branches were interwoven. The only openings in this blanket of forest were blocked by deadfall logs, also bristling with tightly-spaced limbs. I tried backtracking and climbing higher up the slope, where I was able to make some headway before running into the same kinds of barriers. This was starting to look sketchy.

But I was fresh – I’d had a good night’s sleep, and the two days of driving had made me desperate for a good hike. So I accepted the challenge and continued the process of scouting a way through the maze, hitting a barrier, backtracking and climbing down or up to look for a way around, advancing another fifty or a hundred feet before meeting another blockage of limbs or deadfall. Rarely, I would notice sunlight on a wider spot in the canyon bottom where the willow thickets thinned out, and edge downwards to see if a path might open up there. This canyon was filled with birds and their songs; I often saw the black, white, and red flash of woodpeckers, and reaching a bend in the canyon, I looked up to see a pair of golden eagles smoothly cruising from one ridge to the other.

But where the willow thickets briefly vacated the canyon bottom, they were usually replaced by stands of wild rose which could become just as impenetrable. All the backtracking, climbing, and searching was hard work, and my pack was feeling heavier the farther I went.

According to the map, there was a falls up ahead, a thousand feet above the canyon mouth, halfway to the plateau, which had been part of the attraction of this route. And not far past the end of the road, I had begun to hear a stream tricking deep within the willow thickets. Eventually I came to a spot where the willows thinned, and I could get close enough to glimpse a ribbon of black water running through a deep hollow. This meant I could stay as long as my food held out, without having to rely on carried water – I had brought only enough for one day.

I sampled some wild rose hips – they were shriveled but still mouth-wateringly sweet. And after having constantly crossed sheep-or-deerlike tracks and scat, I came upon some unfamiliar, much larger pellets – elk? They certainly weren’t horse or burro.

The sun seemed to perch at the head of the canyon, noticeably lower than at my more southerly home, and creating a strong glare that made it hard for me to scout ahead. But eventually I caught a glimpse of tall, sheer cliffs rising up there, creating a narrows that was choked with trees, willows or brush. I guessed the falls must be in there, and I would have to climb around it.

Night Above the Falls

I fought my way up to the first level of cliffs, where I found a majestic old juniper sheltering a little ledge, then carefully ventured out to the edge. I could hear the falls, a hundred feet below – in this season, only a trickle – but all I could glimpse down there was thickets of golden willows and wild rose.

I continued climbing and fighting my way through the mazelike forest and loose rocky slope above successive levels of cliffs, and finally emerged fifty feet above the second, higher part of the canyon. Now I had a better view of the bare “treeline” slopes far ahead and high above, which I assumed led to the plateau, but the sun was setting, the canyon sides seemed steeper and the vegetation even more congested up here, and I realized with a sinking heart that I wasn’t going to be camping on the plateau tonight.

My pack was really weighing me down, and I was exhausted after only three hours of hiking. This expedition was looking like a bust. Maybe these mountains really were impenetrable – a place for animals but not for people.

With virtually no level ground, dense thickets along the creek, and low branches and deadfall in the forest, finding a campsite for the night was daunting. After 20 minutes of fruitless scouting, I finally settled for a tiny, fairly level spot between a fallen pinyon log and a thicket of mountain mahogany, just big enough for my sleeping bag. As the dark descended, I gathered up pinyon duff in my old army-surplus poncho and built up a reasonably comfortable 6-inch-thick pile to sleep on. While gathering, I became aware that the ground was dotted with this season’s green cones, open to reveal a bumper crop of pine nuts. Fortunately there was little wind. I ate a meager cold meal of jerky, nuts and sesame sticks, and went to bed as it became full dark, listening to the occasional rhythmic hooting of some unknown bird.

But I couldn’t get to sleep that night at all. I was physically comfortable, but mentally restless. What would I do in the morning? Would I really give up and turn back, after all these years of dreaming of that plateau and those lakes? Finally I decided I would leave my overnight gear here by the stream, and try the rest of the climb as a day hike, with a lightened pack. I would start by heading straight up to the ridge above the canyon, and follow that to the summit. That couldn’t be any harder than fighting through the canyon bottom, and it might even turn out to be easier.

Final Climb

After a long night of tossing and turning, and sporadic hooting from the unknown bird, I started noticing the sky getting lighter. Disgusted with myself, I got up, had a quick breakfast of dry granola, packed for a day hike, and rolled everything else up in my poncho to stash nearby in the crook of a pinyon. I tried to memorize the location by orienting in relation to the plunging ridgeline across the canyon. Hopefully it wouldn’t be too hard to find on the way back down. As sunlight crept into the canyon bottom, a spotted towhee, a bird I know well from home, flitted into some nearby brush and began rummaging around. It seemed a little bigger, with slightly different coloration than what I was used to.

But my plan to climb the ridge turned into a fiasco. After climbing several hundred vertical feet, and threading a maze of branches across a small plateau, I came to its edge and found myself looking across a deep gap to an even higher ridge looming above me in shadow and curving around toward the “treeline” crest in the far distance. I had climbed in vain and would need to drop hundreds of feet back into the canyon. There, more willow thickets awaited me, and ahead, the canyon sides seemed even steeper than before. Was this worth it? Even if I managed to eventually fight my way to the plateau, I would then have to fight my way back down. Should I admit defeat, and cut my losses?

Still undecided, I descended to the canyon bottom again, eyeing the opposite slope for the first time as a possible alternative. It seemed a little less densely forested, although even rockier. I found a place where I could force my way across, with only minor damage from rose thorns. But only a few yards into the forest on the other side, I ran into completely impenetrable thickets of mountain mahogany. This was madness. I turned and started back across the streambed.

But I’d never forgive myself for giving up. I’d never experienced such a mental and physical battle – repeatedly giving up, then trying again. I tried another way up the opposite slope, and came upon a narrow game trail. Within fifty feet it ended and my way was blocked again. I tried climbing higher and found another game trail. This one led for several hundred feet before ending – the easiest route I’d found yet. I fought my way downslope and encountered another game trail that led a little farther. And so I realized that even if one ended, another one could usually be found, and they all seemed to lead upward. It wasn’t perfect, but I would keep trying.

Eventually I came to a rock outcrop that forced me back across the canyon bottom. Here there was a pool fed by a tiny waterfall, where I refilled my water bottle. This was some of the sweetest water I’d ever tasted, and probably didn’t even need treatment – there were clearly no livestock in this drainage, and the road in had shown no evidence of human visitors for many years. Not far above that, the stream was covered with a thin crust of ice from the night before. I looked up. While I’d been occupied at ground level, heavy clouds had drifted over the canyon, and wind had picked up. It started to look like I might be in for some weather – not good conditions for exploring an exposed alpine plateau.

But it was still early, and at this point, I could actually see an open slope up above. Just a little more forest to penetrate! Sagebrush had been appearing all the way up this canyon, in small clumps in clearings between deadfall, but now I could see that the bare-looking “treeline” slopes at the head of the canyon actually consisted of pure stands of big sagebrush. And as the forest thinned out, game trails began appearing everywhere, leading upwards through the rocks and brush, copiously littered with what looked like mountain sheep scat, both new and old. Leaving the canyon bottom, I cut diagonally up the opposite slope and finally emerged from the forest. The game trails were steep, and there was loose rock everywhere, but the view above, seeming to be the head of the canyon, beckoned me on.

Of course, the first horizon you see is never the summit. Following, losing, and rediscovering game trails, I climbed and climbed through the lichen-encrusted rocks and sagebrush. A strong, cold wind blew up here, and clouds still massed darkly, blocking the sun. I approached another stretch of forest, this time stunted pinyon, mountain mahogany, and the occasional limber pine with its smooth, pale bark. The wind was full of the sweetest, most pungent herbal aroma I’d ever smelled in nature. It must have been the sagebrush, but it seemed almost too overwhelming to be real. The stunted trees with their interwoven branches became too dense to penetrate, so I had to climb higher until I found a break in the forest. Still the summit rose higher ahead of me. I emerged into another stretch of sagebrush-lined canyon, with no end in sight.

The Lion and the Stallion

But after following game trails around another shoulder of ridge, I suddenly found myself looking down onto the promised land: across a broad hollow appeared the edge of the plateau, where I could see the streambed literally spilling over the edge, between boulders, into the actual head of the canyon, like the spout of a jug. Behind it, I could see a grassy meadow, a beautiful golden color. All I had to do was carefully hike down a few hundred rocky feet and I’d be there.

This plateau is unique because it’s on the summit of the range, at 9,000′ elevation, like a table in the sky. The actual peak of the range is only a little bump past the south edge of the plateau, seldom even visible when you’re up there. As I walked out onto the plateau, between stands of big sagebrush and through golden grasses, I really felt like I was on top of the world. It felt like steppe country. The level meadows are cradled between rolling arms of low upland only a few yards high, but you can’t see beyond them to other parts of the plateau. The ridge I’d entered over continues as a rocky rampart across the north edge of the plateau, and the dry streambed cuts across the plateau as a ditch a yard deep. Following this ditch upstream, I came upon more pronounced game trails, trampled in the grass on either side.

As I followed one of these trails toward a narrow pass though the cradling upland, grass gave way to tall stands of sagebrush, and approaching a bend, I suddenly glimpsed the back of a big tawny animal leaping out of the trail ahead, into the sagebrush. I stopped and waited for it to emerge from the other side of the thicket and flee up the low slope fifty feet back of the trail. But it didn’t. It stopped in the sagebrush, hidden just off the trail.

That immediately puzzled me. What could it be? A deer or antelope would’ve continued fleeing. I continued walking to the spot where I’d seen it last, and made some coyote howls, facing where it had disappeared into the brush. Suddenly I realized that it couldn’t have been either deer or antelope. If it had been male, with horns, I would’ve noticed. And if it were female, it wouldn’t have been alone, and wouldn’t have stopped to hide in the brush. Nor would a coyote – and this animal had been bigger than that anyway. It had to have been a mountain lion, and now it was hiding in there, waiting to see what I would do.

The epic struggle to get up here had put me in a determined, or maybe even a desperate, frame of mind. Retreating would send the wrong message – I felt the only thing I could do was keep going. Once through the little narrows, the meadow opened out again, into a big basin of cropped grass. Here, I found bleached bones, probably from deer or antelope, scattered everywhere. With its stands of sagebrush for cover, this place must be paradise for a mountain lion! I walked out into the center of the meadow, and suddenly came upon a huge pile of horse shit. Wild horses! I’d never seen anything like this. Why would they all shit in a pile? It was only later, after searching online, that I learned that wild stallions leave these “stud piles” to mark their territory.

Across the meadow, I saw another narrow pass into another basin, in the direction where I might expect to find one of the mysterious lakes. A dark, rugged cliff loomed in the distance. Following horse trails, I finally came into a new basin and reached the ultimate goal of my trip: the first of the lakes. Far from the idyllic alpine lake the internet article had described, this was just a shallow dry depression lined with cracked white clay and studded with small dried shrubs, with a rampart of stone rising dramatically behind it. It was really just what is technically called a vernal pool, but this plateau was such a strange, extreme place that it seemed okay to glorify it with the name of lake. I wasn’t disappointed – I could imagine it in springtime, filled with snowmelt, reflecting the sky.

But thoughts of the mountain lion kept me on edge. This plateau was no place to linger. A windswept place on top of the world, frequented by wild horses with territorial stallions, strewn with the bones of deer and antelope killed by a resident mountain lion, a lion who was waiting to see what I would do. I wasn’t really scared, because I figured this cat had little or no contact with humans and was probably as mystified as I was. And I was wearing a big hat and a pack, so my neck didn’t present an easy target. But on my way back across the big meadow I grabbed the heaviest bone I could find, and brandished it as I passed the narrows where the lion had gone into hiding. Occasionally halting for a look over my shoulder, I left the strange, fertile yet stark plateau, managing, despite the forest cover, to somehow retrace my steps down to the anonymous spot above the falls where I’d left my overnight gear.

The Mystery Deepens

I spread my poncho over the mattress of pine duff, took off my shoes and socks, and laid down to rest a while. But within minutes I was swarmed by flies. It was 3 in the afternoon and I had worked hard since early morning. I had no way to keep the flies off if I stayed here another night, but if I were going to hike out, I needed to leave right away, in order to get to the truck early enough to have some dusk light to spot landmarks and easily find my way out of the mountains. And then, where would I spend the night? I was really in the middle of nowhere. I was filthy and exhausted from two days without sleep, but after I made it out to the highway, the nearest motel would still be two hours away.

The relentlessly greedy flies made up my mind for me. I repacked my rucksack and struggled through mazes and thickets back down the canyon, to the old dirt road and its abandoned wooden water pipe, out onto the rabbitbrush-lined floodplain and all the way to the gate and my parked truck, with just enough dusk left to drive across the beautiful northern basin and out to the ranch road, as the entire landscape painted itself in infinite shades of blue.

After this adventure, and the late-night ordeal of finding a place to sleep, it took me a couple of days in a motel to rest and recover, but I still didn’t get a chance to process what I’d done, because I was a long way from home, spending money without a further plan, and I needed to figure out what to do next.

It’s only now, while telling the story, that I can begin to uncover what I was up to out there, and what that search for the plateau teaches me, how it changes me.

It clearly wasn’t a “reward” for the months I’d spent in pain and lonely, thankless, time-consuming therapy. It turned out to be more of a challenge to myself – an unconscious way of proving to myself that the surgery, and the recovery, had made me more capable than ever. In fact, this solo backpack into unknown, trackless wilderness was something that nobody I know would attempt to do, not even my younger friends who are clearly in better shape and could certainly manage it better than me.

Spending days traveling to the northwest corner of Nuwuvi territory, visiting their sacred lakes and learning about their rock art, struggling up to a high plateau below which they lived in several, documented seasonal camps – did it all fit together somehow in my lifelong quest for knowledge and wisdom, and to enrich my own art? I wasn’t sure yet. But I knew my quest wasn’t over. At the Pahranagat Visitor Center, a ranger had given me brochures and maps to prehistoric rock art sites all over eastern Nevada…

Wednesday, November 9th, 2016: 2016 Trips, Colorado Plateau, Indigenous Cultures, Regions, Road Trips, Society.

Excitement Rekindled

The old railroad town, hours away from any city or interstate highway, lay sheltered in a high-desert canyon between stark cliffs. The peace and quiet were emphasized by the Union Pacific freight trains that rumbled through the town’s meridian every half hour or so, past the beautiful old Spanish-style depot that faced my motel from across the tracks.

As I rested up from my trip to the lost plateau, I realized I had no further plans, and no idea what to do next, other than a vague thought of revisiting the mountains and canyons of southern Utah. I’d been away from home almost a week, and I was bleeding my precious savings on gas and motel nights, but if I returned now I’d end up having driven more than four days, to achieve only two days of camping and hiking.

My usual fallback is to study the maps for the area I’m in and the direction I might be interested in going, but it was the weekend, so the local BLM office was closed; I’d have to rely on the limited, mostly out of date maps I had and whatever info I could dig up on the internet, using my motel room wifi. And that turned into a conflicted process that took up most of a sunny Saturday, in between walks along the tracks, under the golden cottonwoods, past the quaint, historic buildings.

The Nuwuvi were closer to the center of my mind now than when I’d started this trip, partly because of what they’d said about rock art at the Pahranagat Visitor Center. In response to a general query about maps, the ranger there had passed me a stack of brochures describing natural attractions within an hour or two’s drive of here, and a few of them identified rock art sites I was totally unfamiliar with, all within Nuwuvi territory. However, after all the driving, I also felt obligated to get in some more serious hiking, but the rock art sites were all close to a road. In a few hours of searching I learned that I was surrounded by some promising BLM wilderness areas. One, south of me, sounded really beautiful.

But I had no idea what the camping situation would be like. In town, I’d repeatedly run into groups of hunters in camo buying provisions, and I envisioned driving a couple of hours on a back road only to end up at a trailhead full of ATV trailers and hills ringing with the sound of gunshots, just like back home at this time of year.

Somehow, the hints that I’d picked up at Pahranagat were gradually tugging at my heart and overcoming the appeal of simply exploring wild nature. Remembering something from my deep past, a trip Katie and I had taken almost 30 years earlier, I began to sense the excitement and adventure of rock art exploration – perhaps enriched by what I’d since learned about anthropology and ecology. Since I was already thinking about Utah, I started searching online for more info on rock art sites. As I’d expected, all the really interesting ones were much farther east, and I’d already been to most of them. But there was a famous one, Nine Mile Canyon, that we’d skipped because it was north of I-70, an arbitrary line we’d set in order to stay within our schedule.

Nine Mile Canyon was much farther from home than I’d planned to go on this trip, and would force me onto the dreaded interstate for a couple of hours, but the seed had been planted – and who knew how long it would be before I had this chance again?

County of Carbon

Many mountains intervened! All of Sunday was spent driving through high country, under a dark sky heavy with storm clouds, over mountain passes I hadn’t seen for decades and couldn’t remember at all. In western Utah, a hunter’s pickup truck pulled out onto the highway in front of me, towing a trailer carrying an ATV with enclosed cab. See the mighty hunter, I thought, wafted to his prey in the comfort of his glass-enclosed bubble. Then poorly secured plastic bags began to blow out of the pickup’s bed and all over the sagebrush beside the road. The hunter remained oblivious, cruising well below the speed limit, so I pulled out to pass, and saw that the entire back of his truck was plastered with dozens of belligerent pro-gun and anti-liberal stickers.

In the afternoon, from the interstate, I began to glimpse higher mountains to the south of me holding patches of snow above treeline, in the shadow of the summits. Traffic was blissfully light, but I was still relieved when I was able to turn off onto the two-lane state highway north to Price.

It was a beautiful drive past high-desert farms and ranches and through rural hamlets, up a rising plateau walled on the west by majestic multi-colored badlands, canyons, cliffs and towering terraced mountains. I passed two coal-fired power plants and a sign marking Carbon County. The sun set extravagantly behind breaking clouds and I hit the edge of Price as dark fell.

I had accurately anticipated Price to be even smaller in population than my hometown, but before reaching downtown, I drove past mile after mile of industrial suburbs. It was full dark by the time I turned onto Main Street, where I immediately spotted the large Prehistoric Museum that the rock art websites recommended I visit for guidance to Nine Mile Canyon.

Camping is not allowed in or around the canyon, and during the two days that I used Price as my base, the larger context of this place gradually became clear to me. Carbon County refers to the fossil fuel reserves – coal, oil, and natural gas – that prehistory has accumulated under the ground here. Hence the Prehistoric Museum, or at least the dinosaur half of it. And hence the power plants and all the supporting industries that I passed on my way in, and the flashy new municipal facilities paid for by fossil fuel revenues. Coal built the old county, and natural gas is building the new one.

The people were super nice, from the college-age kids who checked me into my motel, bantering about small towns and enthused about rock art, to the patrons and management of the downtown laundromat where I refreshed my wardrobe while listening to friendly family gossip and well-wishing. Contrary to my impression of Mormon homogeneity, I passed churches of all denominations and saw a poster for a Catholic festival. But the restaurants ranged from mediocre to pathetic, indicating an insular and complacent culture. I only had one decent restaurant meal in the entire second week of my trip.

In the morning, I could see that Price sat in a semi-circular basin surrounded by the broad arc of the terraced Book Cliffs. And here, geology had indeed become an open book, especially after the arrival of the Americans with their heavy machinery, mines and wells.

Creators and Destroyers

You enter Nine Mile Canyon through a high pass lined with aspen groves, dropping into a narrow feeder canyon featuring an inactive coal mine, pungent sulfur springs, and a gas pipeline that parallels the road. A new sign welcomes you to Nine Mile Canyon itself, which is actually 40 miles long, with a newly paved road, a meandering, clear-flowing creek, and a broad, serpentine floodplain occupied by a series of ranches where herd after herd of cattle share pastures with herd after herd of deer. There are a lot of ruins from pioneer days, and a few very modest ranch houses, but all were unoccupied when I was there. I visited on week days, and almost all the traffic consisted of big trucks servicing the natural gas wells on the plateau above, which is reached via dirt roads up side canyons. The main canyon was very recently improved for rock art visitors, with the paved road, picnic areas, and signage added, all courtesy of the Bill Barrett Corporation, which works the gas fields.

For more than a decade before the improvements, the Barrett trucks caused irreparable damage to the rock art by raising lingering clouds of dust from the old dirt road that continually drifted onto the art panels. But for more than a hundred years before that, American frontiersmen – heroes of countless movies – caused even more damage by hacking, shooting at, and obscuring the native art with their own crude graffiti. Nine Mile Canyon is billed as “the world’s longest art gallery”, but after two days of exhaustive exploring, I felt like I’d actually seen more graffiti and vandalism than art.

But that’s probably the unfair result of my own frustration after two days of squinting and peering through binoculars, trying to spot faint markings on the rocks above, while driving short distances along the canyon floor, followed by searching for a place to pull over, and scrambling up a steeper and steeper talus slope to the base of a cliff hundreds of feet above the road. This, while rural and very remote, was a far cry from the wilderness hiking I also yearned to be doing. But as rock art people know, rock art is addictive.

I had no plan beyond exploring the canyon to see what was there. But finding, studying, and photographing the rock art alongside a narrow road with truck traffic proved to be grueling and stressful. With 40 miles to explore, I felt I had little time to contemplate each panel, so I mainly focused on taking pictures to examine later. I only made it a third of the way down the canyon on Monday, and assumed I would leave the area Tuesday. But when I woke up refreshed the next morning, I realized I would have to return and finish. Instead of picking up where I left off, I drove all the way to the end, had lunch and drank a beer, and that made all the difference. The second day was more relaxed and more insightful.

But as I returned to town, I was overwhelmed and perplexed. Nine Mile Canyon is considered a center of the so-called Fremont culture (named for Utah’s Fremont River), and most of the art I’d seen is attributed to them, from roughly a thousand years ago. Although many of the petroglyphs had impressed me, I was predisposed to think of the Fremont as the backwards neighbors of the Anasazi (now called Ancestral Pueblo) who left the famous cliff dwellings of the Colorado Plateau, farther south and east. The Fremont had lived in primitive-sounding “pit houses”, and on the archaeologists’ timeline they fell between the archaic Basketmakers, creators of the most impressive rock art in North America, and the advanced, city-buildling Puebloans.

After devoting two days to their rock art, I decided it was time to refresh my knowledge of the Fremont, by visiting the Prehistoric Museum in Price. Did their culture deserve a closer look? Maybe I’d even learn something that would add focus to my – so far haphazard – wanderings.

Friday, November 11th, 2016: 2016 Trips, Colorado Plateau, Indigenous Cultures, Regions, Road Trips, Society.

Rising From the Pit

Rising on a chilly morning in Price, Utah, after spending two days frenetically exploring the prehistoric rock art of Nine Mile Canyon, I was determined to learn more about the so-called Fremont people who had apparently created it a thousand years ago. When I left my motel, heading down Main Street to the Prehistoric Museum, I saw snow on the high ridge above the Book Cliffs to the west, product of the storm clouds that had moved over the area yesterday while I was out in the canyon.

Mostly alone in the silent archaeological galleries of the museum, I eagerly studied the exhibits, which focused primarily on the ancient Fremont culture that had spanned most of Utah, while providing both more ancient (Ice Age) and more recent (Native American tribal) context. Information, while new to me, was provided in fairly conventional forms, leaving me to gradually absorb and process what I’d learned, during the next few weeks, and to eventually add insight from my own eclectic research and work.

But one revelation happened immediately when I walked into the main gallery. Straight in front of me at the back of the hall, illuminated by spotlights, was a full-scale reconstruction of a Fremont pit house from Nine Mile Canyon.

When I first encountered the Fremont legacy and archaeological theories in the late 1980s, during my rock art expedition with Katie, I thought of them as less interesting, more primitive, and therefore doomed neighbors of the Anasazi who lived in cliff dwellings to their south and east. And when I heard about Fremont “pit houses”, I dismissed them as crude animalistic nests. Who would want to live in a pit?

But as I walked toward the reconstruction, it came alive for me, and I suddenly saw myself living there willingly and happily, snug in a spacious, vaulted open plan shelter that would be warm in winter and cool in summer, with everything I needed organized and within reach. This was much better than the supposedly more advanced Anasazi’s ancestral pueblo cliff dwellings with their cramped, dark, uncomfortable warrens.

I also immediately recognized other vitally important implications that made the Fremont more interesting and more inspiring than the Anasazi. And while methodically reviewing the surrounding exhibits, I learned to my surprise that one theory of the Fremont’s “demise” is that they eventually merged with the Nuwuvi and other adjacent tribes that were migrating into Fremont territory as part of the hypothetical Numic Expansion. So the Fremont may be an important part of the story of the Nuwuvi, the native people I’ve been closest to for decades.

Finally, an information panel attached to the museum’s “Pleistocene hunters” diorama described the scientific controversy over the cause of the famous Quaternary Extinction Event. One old theory, popularized in the media, holds that Native Americans hunted the Pleistocene megafauna to extinction. But native technology was clearly never powerful enough, and native populations never large enough, to achieve that. The dysfunctional compartmentalization of science ensures that many contemporary biologists cling to the disputed theory that makes them feel better about their own work, regarding natives as irresponsible savages.

Houses of Peace

During the years after Katie and I explored the Anasazi cliff dwellings of the Colorado Plateau, I was bothered by how cramped, uncomfortable, and inconvenient they seemed. I could hardly believe they had been used as full-time dwellings, but even if they had, their hidden, often inaccessible locations and fortress-like construction suggested that, far from the crowning achievement of an advanced civilization, they were more likely the refuge of timid people who lived crowded together like ants, with no privacy, in constant fear of attack.

The misleadingly named pit houses of the Fremont, on the other hand, were clearly the spacious private homes of families who were living in peace, at ground level, unafraid of attack. They had somehow managed to develop a peaceful, egalitarian, and sharing society over a wide area to the north of the Puebloans, whose conflicted and violent culture would cause the invading Spanish so much grief in later centuries.

The museum’s description of archaic social organization, informed by the social organization of recent desert tribes like the Nuwuvi, shows that the egalitarian and communal culture ascribed to the Fremont was not only sustainable, it was sustained for 7,000 years in the Great Basin and Mojave Desert, while Anglo-Europeans and other so-called advanced cultures developed their extremely hierarchical, unjust, unstable, and incessantly warlike nation-states and empires which would come to dominate the entire world. And the Fremonts’ material remains show that native ecology likewise remained stable and sustainable through those thousands of years. The only important changes during that long period represented resilient adaptations to changing climate, as communities became more or less settled or nomadic, more focused on agriculture or foraging and hunting.

In essence, the Fremont were part of a timeless tradition following natural cycles, so the Anglo-European scientific bias toward technological progress, origins and endings, ages and eras, carbon dating and linear timelines, is misleading and inaccurate. Forget the 7,000 years. Fremont are today and always.

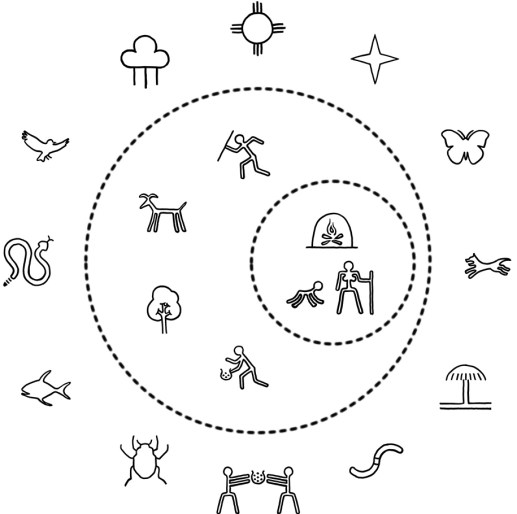

By the Numbers: Rock Art Motifs in Nine Mile Canyon

After returning home and reviewing my rock art photos, I began to realize I could only justify the effort I spent in the canyon by trying to make sense of the rock art panels in retrospect. And I could only do that by thoroughly analyzing the content of the panels – making up for my rush through the canyon, my inability to hang out and contemplate each panel, my failure to give them the time they deserved.

So I reviewed the photos over and over again, identifying and naming the motifs that seemed important to me, and counting them to get a sense of their relative importance or value to the artists themselves. I know this is one way in which archaeologists have studied rock art, but I didn’t want to distract or bias myself by first referring to the archaeological literature. I needed to go on the basis of my lifelong experience as an artist, and the experience with symbolic communication that I’ve acquired during the 15 years of my Pictures of Knowledge project.

I analyzed 56 panels in total.

[table id=1 /]

Rock Art Questions and Insights

What did the panels consist of?

- Humans appeared in only about a third of the panels, indicating that the artists attached more value to nonhuman phenomena, and were not strongly anthropocentric, like Anglo-Europeans

- There was no sign of conflict or violence between humans

- Humans were overwhelming depicted as asexual, indicating a lack of gender bias

- One in every 7 humans depicted was given horns or antlers, indicating superhuman (male game animal) power, and suggesting that showing this power was an important motive for creating some of the art

- Only one of these empowered humans was shown as male, with a penis, suggesting that “shamans” were not predominantly male

- Less than 10% of the humans depicted were shown as hunters, challenging the conventional assumption that rock art represented “hunting magic”

- In Fremont art, as in other desert rock art styles, the human torso is sometimes exaggerated and/or filled with symbols or patterns. Referring to the Fremont clay figurines, these decorations are sometimes assumed to represent clothing, fashion or decoration. But the torso can alternatively be seen as a container for symbolism, for example clan insignias, personal identification, or signs of power.

- The famous “Great Hunt” panel was unique among the panels. This in itself suggests that big game hunting may not have been as important as it is normally assumed to be. Or even that this panel could be a later fabrication…

- Almost half the panels included bighorn sheep, reinforcing the importance of this game animal, later driven to extinction by Americans

- Sheep were shown as being hunted in only 20% of the panels in which they appeared, suggesting – surprisingly – that their importance went far beyond the act of hunting

- More than a quarter of the sheep panels showed them being herded by dogs, whether for hunting or not. One would think that mountain sheep could quickly escape uphill in these rocky canyons, unless the hunts were arranged in a location where the hunters were somehow blocking their escape. The dog images surprise me, because I’ve never encountered any mention of the use of hunting dogs by prehistoric societies in the Southwest.

- Only one possible and one likely plant image appeared, suggesting, surprisingly, that farming and foraging were not important to makers of rock art, or not at the time rock art was created

- However, could the rectilinear dot patterns represent garden plantings or crop fields?

- Based on my experience, both abstract and representational motifs were similar here to those used throughout the Great Basin and Mojave Desert, reinforcing the sense of cultural continuity and timelessness already cited above under “Houses of Peace”

- Panels ranged from single motifs, to symbolic compositions, to seemingly random collections, and finally to obvious narratives

- As in my Pictures of Knowledge work, symbols can be simple or compound (combinations of multiple simple symbols)

How were they made?

- Were they made continuously for hundreds of years, or only at certain times or during specific periods?

- Were petroglyphs male-created, and pictographs female-created, or were they made by both sexes?

How were they used?

- As a tool for teaching youth and perpetuating knowledge and wisdom? This resonates most strongly with my own experience in the Pictures of Knowledge project.

- As a record of important events or configurations for remembering, emulating, and reinforcing social bonds?

- As a visual model of a proposed goal, for study and evaluation?

- As a plan for a proposed project?

- As an evocation or invocation of ancestors, animals, or spirits they were seeking to benefit from?

- As maps or directions?

- As clan symbols or markings of territorial claims?

Sunday, November 13th, 2016: 2016 Trips, Colorado Plateau, Indigenous Cultures, Regions, Road Trips, Society.

Rain Angels

When I checked out of my motel in Price and headed over to the Prehistoric Museum, I had been planning a quick review followed by a drive south of I-70 into more familiar, and well-loved, territory on the way back home. But in the museum, while having my eyes opened to the ancient Fremont culture, I’d run across a map to rock art sites with a thumbnail photo that intrigued me, from a site north of 70 that I’d heard of but knew nothing about.

On the way there, in late morning, I crossed the high plateau of the San Rafael Swell on a wide, well-maintained gravel road, past lonely oil wells, the occasional corral, and two surprisingly unskittish pronghorn antelopes, finally descending into the head of a canyon. Winding sharply back and forth between rising cliffs, the canyon quickly acquired monumental, spectacular dimensions. Just as driving became a challenge – because my head kept whipping from right to left in amazement – I began noticing dirt side tracks that would certainly lead to informal campsites. And then, around a sharp turn in the sheer thousand-foot cliff beside the road, the rock art appeared, and I pulled into a small dirt parking lot surrounded by wood fencing, information kiosks, and pit toilets.

It’s always a challenge when heart-stopping beauty appears as you’re driving. And it’s a tragedy that a road was built through this canyon, so that some of the most impressive art in North America is only a few yards from the automobile, one of the most destructive of our myriad destructive machines. The overhanging cliff was awash with midday sunshine, and the paintings were dimmed by glare, but my heart felt about to explode as I humbly approached, craning my neck, as the artists intended we should, to look up at the larger-than-life images hovering above in the golden light.

The specialists call this style “Barrier Canyon”, and it’s attributed to the vaguely defined “late archaic” culture that may have been ancestral to the Fremont in most of Utah. Archaeologists say these people lived in pit houses, practiced a mix of hunting, foraging, and limited farming, and relied on baskets as containers, on the brink of learning to make pottery. That’s about all that is suspected of them.

But the museum in Price implied that these people were part of the continuum from Paleolithic to first-millennium Fremont and recent Nuwuvi, which seems intuitive to me, except for the fact that their art is radically different from what came after.

As an artist, I find this work the most compelling ever created on this continent. It’s a heart reaction, not the result of analysis, but it begins in the recognition that the art is integrated with the landscape that was these people’s home, and it appears to have been perfect, and timeless, from the start. When I attempt to analyze, I see that it’s overwhelmingly anthropocentric, and intended to impress, if not intimidate, the viewer, which disturbs me on an intellectual level. In general, Barrier Canyon artists chose monumental sites that would emphasize the scale of the art and the smallness of the viewer, and we Anglo-Europeans tend to unconsciously respond to them the way we would to the interior of a cathedral.

Specialists have conjectured that these larger-than-life humanoids represent ancestor spirits and shamans – in this case, someone with rainmaking medicine. What does it mean to have a stretched, or stretching, torso, and minimized head, arms, and legs? I’m still working on that, but on the most basic level, it suggests transformation and transcendence of the body, perhaps toward and beyond death, to what we generally call the spirit world. This unique style of art may have been made across a broad geographical area during a specific period of time when people were under stress and needed the help of powerful spirits, but in other traditional cultures, those spirits have been recognized in nonhuman form: clouds, lightning, serpents and other animals – since subsistence cultures know and accept that humans are totally dependent on natural ecosystems for our sustenance.

And why was this powerful style of art made only during this early period, and not afterwards, when people surely had the same ability? The vast majority of rock art in the West is either didactic or obscurely abstract. Barrier Canyon art remains a compelling mystery, just representational enough to suggest we might be able to understand it. As Katie and I discovered, hallucinogens can provide the best introduction to rock art, and I deeply regretted not having any this time around.

Realizing that I couldn’t effectively photograph the art in full sunlight, I got back in the truck and scouted campsites both up and down canyon, settling on one about a mile and a half up-canyon from the art. I was late for lunch, and put something cold together, then headed back into a side canyon for a day hike toward the cliffs above. I didn’t go far, but got in a good climb up successive ledges and talus slopes, and the always welcome experience of being totally dwarfed by a landscape of stone.

One thing that surprised me here was the low angle of the sun at midday, noticeably lower than at home – but that was emphasized by the towering cliffs. Warm in the sun but cool in the abundant and long-lasting shade, my campsite turned out to be frigid until late the next morning.

In late afternoon of that first day I walked back down the road to the rock art site, and found a young rock climber from Moab who had soloed a nearby stone tower and stumbled upon this place unexpectedly on his drive home. I enjoyed and shared his awestruck reaction as we both tried for good photos.

As dark fell, after dinner, I took short night walks up and down the road, just for something do. The little traffic on this remote road, the occasional truck or RV, ended at 8 pm, and I went to bed not long after, sleeping well until the freezing dawn, after which it took hours for the sun to rise above the cliffs enough to warm my campsite and freshen my sleeping bag where I’d draped it over sagebrush. Then I made a last brief visit to the rock art, and headed south out of the mouth of the canyon.

The photographs below are impressive, but you really need to be there. As an artist, I seek experiences like this, but I actually find it hard to remain long in the presence of this ancient but timeless work, in this remote and intimidating, yet in many ways idyllic, place, without, literally, fainting from an excess of emotion.

Latterday Holy Land

I drove through familiar country at the eastern edge of Nuwuvi territory with less than my usual attention. It was a long drive, and I’d decided to “quit while I was ahead” – I’d seen and learned far too much to process already. And a storm was moving over the region, the forecast was for rain, and the cold, lonely morning in my canyon campsite decided me on a motel room for the night, followed by an even longer drive home the next day.

However, in the morning, before leaving Utah, I decided to make one last detour. Thirty years ago, Katie and I had been especially impressed by some petroglyphs and modest ruins here, near the epic sweep of Comb Ridge. I’d tried to relocate them several years ago, but failed. This time, guided by a brief note on a rock art website, I followed a dirt road to its end and a trail that led down the cliff face. I immediately recognized the rock art, and glimpsed ruins across the canyon under an overhang, but the place wasn’t exactly what I was looking for. Maybe my memory was rusty. This would have to do as a final contact with prehistory.

The first panel, above a ledge below the east wall of the canyon, exhibits a distinctly more ordered composition and polished execution, not to mention a more representational style, than the Fremont work in Nine Mile Canyon. These petroglyphs, and the “cliff dwelling” ruins, are associated with the Anasazi – now termed Ancestral Pueblo – culture, but the elongated human figure may reflect some influence of the archaic Barrier Canyon style. The imagery includes a prominent, elegant crane – which would’ve been found along the San Juan River a few miles south – botanical or horticultural imagery, and the first fish petroglyph I’d seen on this trip – a native chub, now endangered by the arrogant habitat engineering of us Americans.

The two ruins tucked away, almost invisibly, under the canyon’s west wall, also differ dramatically from each other. The larger is mostly adobe and has “melted” almost beyond recognition, while the smaller, of drystone construction, remains evocative of domestic utility, but on a very “tiny home” scale. Specialists say that Ancestral Puebloans were short – men averaged 5′ 5″, women 5′ – but I’m not much over 5′ 5″ and I would’ve been uncomfortable sleeping in any of these rooms. So while I find cliff ruins evocative and their architecture ingenious, I can’t identify with their culture.

The rock art above the ruins follows a narrow, vertiginous ledge dozens of feet above the ground, and reaching it in the first place would’ve required a ladder, making this the least accessible canvas I’d seen on this trip. And the style of these petroglyphs more closely resembled Fremont, suggesting a different time frame and origin from the panel across the canyon. A number of big robust birds without topknots – maybe ducks or geese – some curious little humanoids with doglike ears, and at least one turtle.

The mixture of styles here, in conjunction with the ruins, presents a cultural mystery, perhaps indicating completely different societies using this site during different time periods.

As I was heading back across the canyon, a rustic-looking retired couple emerged from the canyon bottom and began examining the ruins. I waved, then watched as the man clambered up the sloping cliff beside the stone house holding a camera and the woman went inside the house and climbed up into the “bedroom” so he could take her picture through a window in the side. Climbing on these ruins is strictly forbidden, because it accelerates their deterioration, so I was shocked, but was reluctant to say anything since these strangers obviously intended no damage.

But after returning to my truck, I realized it was time for lunch, so I made a sandwich and waited for the couple to show up.

The clouds overhead were darkening and wind was picking up. When they arrived at their SUV, I walked over, assured that I meant no disrespect or criticism, but politely warned them that a ranger or archaeologist wouldn’t tolerate climbing on ruins, and explained why.

They listened with blank expressions. Then the man smiled and asked, “Have you read the Book of Mormon?”

“No…”

“Well, you should, because it talks about the Lamanites, the people who built these ruins. You know we white folks are the Nephites, and the Native Americans the Lamanites whose land this was before we showed up.

“Science says ‘this is the way it might have been’, but the Book of Mormon tells the truth of how it was. And after visiting places like this, I’ve prayed on it, and more of the truth has been revealed to me.

“That’s what you should do, read the Book and pray on it.”

He was still smiling, but more intently.

“Well, my brother’s read the Book of Mormon, maybe I’ll ask him for some pointers.”

He mentioned a rancher friend whose land contained unexcavated ruins, and said he was looking forward to studying them at his leisure – presumably without the prohibitions that applied to public land. We wished each other safe travels – the wind was beginning to splatter rain all around – and I got in the truck to drive south toward home.

I’m respectful of all religions because I see their primary function as unifying a community under a single code of behavior so they can support each other, mediate conflict, and mitigate abuse. I see some good things in Mormon principles, but I reject any form of proselytizing or missionary work, and I note that Mormon society shows an unfortunate embrace of capitalism, consumerism, and technological progress – mirroring the dominant secular society.

I’m also unorthodox in my attitude toward archaeological ruins. Whereas vandalism to rock art sickens me, I view ruins as future resources to both responsible humans and the ecosystem at large. Vandalism by urban consumers is pointless and wasteful, but the reuse of both historical and prehistoric materials found in ruins by people in subsistence communities is fair and just.

Thanks to these folks, I didn’t have to pray for a revelation. While driving away, I realized that to a Mormon, exploring the prehistory of the Utah homeland is like a mainline Christian visiting the Mideastern Holy Land. The Book of Mormon provides the basis, and visiting the prehistoric sites of the Lamanites can add insights – revelations – beyond what’s in the gospels, taking you deeper into your religion, perhaps closer to God, and possibly more committed to principles of good behavior.

Closing the Circles

I drove through rain, often heavy, on and off, all day, giving my arm and windshield wiper controls a real workout. I’d initially expected to stop for the night, wanting to avoid driving the last hundred miles, with the risk of deer crossings, in the dark. But it was time to be home, so I just kept driving.

I always love coming out of the pass into the Nutrioso Valley of Arizona with a full view of Escudilla Mountain looming like a whaleback. Snow was sprinkled on its north slope, and then as I reached midway down the valley I noticed a rainbow to my left, and pulled over. The speeding Arizonans in their big new trucks and SUVs raced on, oblivious, as I tried to capture a panorama of what turned out to be double arches, perhaps the most glorious I’d ever seen.

Later, coming down out of the mountains in the dark, still an hour from home, I began to see broad, almost continuous explosions of lightning over toward Silver City, as if a major war were underway. It faded, then resumed, then finally moved off, as I got closer. A half hour from home, I saw a bright falling star drop quickly to the horizon directly ahead.

This trip had started as a challenge to my precious hiking ability, with the epic climb to the Lost Plateau, but along the way the Nuwuvi reached out and grabbed me, reminding me that their heritage lived on in the timeless desert culture and its vibrant rock art. I was led to connect the “Ice Age” prehistory of the Great Basin and western Rocky Mountains seamlessly with the natives of my Mojave Desert, learning much more about their sustainable, comfortable, admirable way of life, while highlighting the remaining mysteries of regional adaptations like pottery versus basketry and the singular Barrier Canyon style of art.

The desert and its culture teach me the heresy that time is not a line or a progression from primitive to advanced, punctuated by technological innovations or revolutions that make humans more and more the masters of themselves and their world. For contemporary scientists to proclaim an Anthropocene Era in the history of the earth is like the Nazi’s proclamation of the Thousand-Year Reich: hubris mistaking temporary power for long-term sustainability. The Fremont, who practiced or abandoned small-scale farming as conditions allowed, teach me that agriculture is not an innovation that irreversibly enabled the rise of civilization and the destruction of nature. In an accurate, sustainable, cyclical view of time, agriculture is part of the timeless toolkit of resilient, adaptive cultures, a tool which can be abused at a culture’s peril.

Likewise, native rock rock art is tied to a subsistence ecology, and reflects the adaptation of culture to environment, whereas the Anglo-European art tradition is driven by technological progress in the quest to dominate and control nature and increase human power and convenience at the expense of the ecosystem, resulting in “advances” and “revolutions” in which previous art styles become obsolete. The Anglo-European art tradition – which has progressed through Classicism, Romanticism, Impressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Conceptualism, Postmodernism, etc. – can’t be timeless like rock art. It’s always time-bound, transformed by the Age of Empire with its rifles, cannons, and shipping fleets exploiting distant, exotic cultures, transformed by the invention of photography, movies, plastics, video, the computer, the internet. We speak of the “international art scene”, but even in places like China, art’s forms and movements remain the forms of the dominant technological powers.

Native rock art long ago weaned me from the value system of the dominant society, in which art is technology-driven – a commodity in a competitive money economy, a status symbol, or an entry in the public discourse of high civilization – the misguided discourse of a dysfunctional, failing society, dominated by alienated experts and authorities. While I carry a lot of baggage from the Anglo-European tradition, including deep sympathy for my struggling brothers and sisters in the fine art underground, I truly value the abstract petroglyphs of the Nuwuvi, as well as the ancient Barrier Canyon paintings of the Basketmakers, far more – as art – than the work sanctioned in our highbrow art schools, media, galleries and museums. I really do. My own art will never be more than a feeble attempt to emulate those natives who had a critical, respected role in a timeless society.

Rockets and Robots: Engineering Without Understanding

Tuesday, November 29th, 2016: Problems & Solutions, Society.

Download PDF for printing & e-readers

Contents

1 • Overview

2 • My Experience With Rockets, Robots, and Engineering

3 • Blindsided: Brave New Heroes

4 • The Power and the Glory: Rationalizing Desire

5 • The Cultural Baggage of Tech

5.1 • Anthropocentrism and Dominion

5.2 • Urbanism and Alienation

5.3 • Linear Time and Progress

5.4 • Individualism and Free Enterprise

5.5 • Exploration and Imperialism

5.6 • Reductionism and Mechanism

5.7 • Invention and Innovation

5.8 • Statism and Coercion

5.9 • Media and Misdirection

5.10 • A Perfect Storm of Fallacies

6 • Humbled By the Mysteries: Discovering Context in Ecology and Anthropology

6.1 • Natural Ecosystems

6.2 • Healthy Societies

7 • Vicious Cycles of Engineering and Technology: How Dominant Societies Fail

7.1 • The Engineeering of Habitat

7.2 • Vicious Cycles

8 • Engineering Without Understanding

8.1 • Unquestioning Idealism

8.2 • Medical Technology: The Ultimate Rationalization

9 • Robots: Weakening and Killing Us, Threatening Nature and Society

10 • Space Exploration and Colonization: War on the Sky

11 • What We Can Expect

1 • Overview

As a child, I was inspired by the space program of the Kennedy era. I loved science fiction, I was a prodigy in science as well as the arts, and I studied hard science before obtaining an engineering degree. But as I matured and gained experience with both nature and society, working in the field with biologist and anthropologist friends, I became aware of major historical fallacies underlying and undermining all the institutions of our dominant culture, and saw at first hand the widespread, ongoing destruction to local communities and natural habitats caused by technological innovation and exploration. Specialization ensures that engineers and other technologists are relatively uneducated in the broader context of the systems into which they introduce their creations; instead, they accept without questioning the historical fallacies of the dominant society, relying on these fallacies to rationalize and justify their work. Consumers, equally victimized by historical fallacies and misdirected by media, eagerly embrace the stimulation and personal power offered by new technologies, turning their backs on the social systems and natural ecosystems they need in order to thrive.

2 • My Experience With Rockets, Robots, and Engineering

I used to be an astronaut, a spacewalker on the International Space Station…I remember holding onto a handrail on the outside of the Station…The terminator flicked over us, and, in the deeper darkness ahead and below us, I could see a huge lit-up city, glued to the curved Earth, sliding up over the rim of the world to meet me…To me, the city lights below represented human energy and hope. Most people work hard to better their own and their families’ lives by struggling to get a bit more than they have. It’s a laudable impulse; it’s what got us out of caves and into villages, towns, and cities. This process has propelled civilizations forward: art, philosophy, engineering, and science all came from the cities where people interact, discuss, argue, and push the human reach a little further. (Piers Sellers, The New Yorker, 2016)

Like many boys, I grew up reading science fiction, and like most Americans, I was inspired by the space program of the Kennedy era. My father was a rocket scientist who became a rocket engineer, and like him, I excelled in science and math. At the age of 12, at home, I built a laser from scratch. But I also excelled in – and loved – the arts, and in my adolescence, as the 1960s ended in cultural revolution and disillusionment with science and technology, I was torn by inner conflict between the arts and sciences.

I started college in fine arts and philosophy at the University of Chicago, but at the age of 20, financially dependent and insecure, with the national economy in recession, I switched to hard science – physics, chemistry, computer science, earth and space science – with a focus on advanced mathematics. However, I was still working at minimum wage and living in poverty, and desperate for some kind of career, I eventually transferred to a nearby engineering school.

After finishing my B.S., I moved to California to complete a Master of Science degree at Stanford in mechanical engineering, specializing in dynamics, the science of motion and change, which involved especially challenging mathematics. My graduate advisor and mentor had achieved international renown by reformulating the classical equations of motion for the computer age, and had become one of the heroes of the emerging science of robotics. But he’d also done groundbreaking work for NASA, and together we developed a novel technique for the difficult deployment of synchronous satellites into a low earth orbit.

But I was still writing and making music and art, and at that point, the artist in me had had more than enough of that left-brain dominance. Henceforth, I would give all my heart to the arts and exploit that engineering degree only when necessary to pay the bills.

As it turned out, those bills would never let me get away from engineering and engineers. I worked part-time, sporadically, for an engineering firm over more than a decade, in a role that was regulatory instead of technical, so I could stay out of the “critical path” of responsibility and preserve my precious free time. And then I reinvented myself as a creative professional in the internet industry, and found myself working with computer engineers.

Those engineers have turned out to be good people – well-intentioned, conscientious, sometimes even idealistic – and many of them have become my friends. I hope they will bear with me as I challenge beliefs they hold dear. Although I’m deeply critical of how technologists think, it’s nothing personal – as you will see, it’s actually an indictment of our entire society. And ultimately, it’s an indictment of my own career as a designer of the screens that prevent us from accurately experiencing nature and society in meaningful context.

3 • Blindsided: Brave New Heroes

From robots to medicine to space travel, 2015 was a huge year for science and technology. Tell my daughters at least every month… This is the most amazing time in all of human history to be alive. (Computer engineer, Facebook, 2016)

One Saturday night, I put on a jacket and walked through central Stockholm…I talked with Sebastian, a grad student from somewhere he described as “like Westeros from ‘Game of Thrones.’…Sebastian’s hero was Elon Musk, whom he had never met, but whom he considered a model human being. “I really think I’d take a bullet for that guy,” he told me. (Nathan Heller, The New Yorker, 2016)

After the idealism of the Kennedy administration was followed by a failed war and revelations of environmental destruction and social dysfunction, the space program declined for decades, while robots quietly began filling our factories and hospitals, out of sight and out of mind. As I became immersed in the arts and the exploration of nature, I more or less forgot about science fiction and assumed that the bankrupt fantasy of space exploration was over and done with.

But suddenly, during the past couple of years, science fiction technology has returned with a vengeance, and with a boost from free enterprise. Billionaires promoting robots and rockets have become culture heroes. Billionaire engineer Elon Musk is like a god to millenials, and many of my own peers seem to believe that people like him can save the planet. Musk competes with fellow billionaires Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Larry Page of Google, and Paul Allen of Microsoft to commercialize space and make us a “multi-planet species.” I didn’t see that coming, and it disturbs me more than anything else in our brave new world.

Most engineers are problem solvers. Due to the specialization and compartmentalization of our society, they normally don’t get to formulate, or even to choose, the problems they solve. They just want a challenge – any challenge.

But most engineers grow up on science fiction, and if you give one a billion dollars, he may set out to create the future of robots and space travel that he’s been dreaming of since childhood. That’s exactly what the tech billionaires are doing now – without ever being asked to, and without ever asking the rest of us if that’s what we want or need.

4 • The Power and the Glory: Rationalizing Desire

Musk and other billionaires can easily come up with justifications for their projects, because the world faces problems which are vast and nightmarishly complex, leading to endless confusion and controversy over proposed solutions. Engineers say that robots will improve well-being by liberating people from unpleasant or dangerous labor and by making their lives safer, more comfortable and convenient. Space travel will offer a safety valve for terrestrial population growth, reducing conflict and consumption of natural resources. Musk even proposes that he’ll move everyone to another planet so the earth can recover from the failed engineering of previous generations. And of course, it’s long been accepted in Anglo-European society that our destiny as a species is to continually explore, advance, and expand, to reach our farthest frontiers and our highest potential.

As my academic career revealed, science and technology are thoroughly interdependent, but often with divergent purposes. Science claims to study the complex physical world, unrestrained by practical applications, with the ultimate purpose of fully understanding and explaining nature. Engineers, by contrast, are only concerned with building things that work, in the here and now. Their goal is not to understand complex natural systems, but to replace them with predictable, manageable machines, manufactured materials, and engineered habitats. They begin with imaginary models that simplify reality, making assumptions about what is important and what can be ignored, without ever needing to understand the full context of their problems. And billionaires don’t even need a problem. They’re just trying to make their fantasies come true.

The unquestioned intersection between science and engineering is a self-reinforcing feedback loop. Scientists provide simplified models of nature and an insatiable demand for quantitative data; engineers further simplify the models and use them to design data-generating machines, which scientists then use to refine their models and their questions, leading to the demand for more data and better machines. More and more, science becomes the study of abstracted mechanical data shaped by the machines provided by engineers, rather than the investigation of nature in its meaningful natural context. And as a result, our knowledge of the world becomes more and more instrumental, more oriented toward manipulation and exploitation.

…for subjects that are incredibly complex…the connection between scientific knowledge and technology is tenuous and mediated by many assumptions — assumptions about how science works …about how society works…or about how technology works …The assumptions become invisible parts of the way scientists design experiments, interpret data, and apply their findings. The result is ever more elaborate theories — theories that remain self-referential, and unequal to the task of finding solutions to human problems. (Daniel Sarewitz, The New Atlantis, 2016)

We all suffer when the fantasies of futurists are unleashed in society and in natural ecosystems, neither of which they have studied or seriously tried to understand. Even the smartest and best-educated advocates of technology have simply accepted the word of other specialists about what the world needs. And then they try to make that fit with their science-fiction fantasy of the future.